Perhaps unsurprisingly, the call for a moratorium on new charters has sparked serious debate along familiar pro- and anti-charter lines. Both before and after the vote, several major American newspapers—including the New York Times, Washington Post, and Wall Street Journal—wrote articles strongly opposing the resolution. The Times called the NAACP resolution a “misguided attack” on charters, while the Post snidely urged the Association to “do its homework.” In a letter written to the NAACP, a group of 160 African American education and community leaders from across the country argued passionately against the resolution, writing that the NAACP’s criticisms of charters were based on “cherry-picked and debunked claims” and that a moratorium on new charters would ultimately reduce opportunities for African American students, especially those from low-income families.

Several articles have also appeared defending the resolution. In an article published in Ebony magazine last week, NAACP president and CEO Cornell William Brooks doubled down the resolution’s criticism of charter schools, characterizing charters at one point as “fueling the preschool to prison pipeline.” Steven Rosenfeld also wrote in defense of the resolution in an article for Salon, arguing that both the Times and Post articles were “misguided and uniformed,” and characterizing the charter school industry as “separate and unequal” and a “privatization juggernaut.”

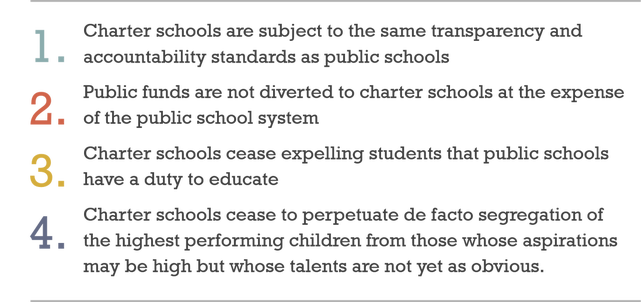

While many of these opinions have strayed a bit toward the extreme, it’s hard to ignore some legitimate points on both sides of the aisle. Those opposing the moratorium cite the positive outcomes and community successes of strong charter schools, such as many of those served by UE; while the NAACP and its supporters seek to rein in charter school networks at their most disastrous, such as those in Detroit or Ohio, ensuring fair transparency, oversight, and accountability for all charters before expansion is allowed to continue. While it’s hard to disagree with the NAACP’s goals for protected public funding for traditional schools and equitable, representative charter school populations (including the inclusion of higher needs students), the question remains whether a nationwide moratorium is an appropriate—or effective—strategy.

One issue I do take with this most recent defense of charters, such as the letter written to the NAACP, is the narrative that charters serve as low-income African American families’ sole hope to “rescue their children from failing schools.” This reasoning undermines one of the founding principles of the charter movement, which justified charter schools’ independence as a testing ground for innovations that could be adopted later in traditional public school settings. While the writers of some of these articles may have lost sight of this aim, it’s something I’ve been proud to have been a part of in our Unconditional Education work. With the program finding its initial successes in neighborhood charter schools, and expanding later into district schools through partnerships with San Francisco, Oakland, and West Contra Costa Unified School Districts, the arc of UE’s growth has in many ways fulfilled this piece of charter schools’ intentions. As such, the flexibility that charters have granted the UE program in finding its own roots is hard to ignore when considering my own stance on the NAACP’s resolution.

Sean Murphy, Assistant Director of Program Assessment and Evaluation

RSS Feed

RSS Feed